Al Qamar Academy, Chennai

August – September 2016

Small Science – Classes 3 and 4

From inquiry to learning – 1

As adults and educators, when we see the Small Science Workbook, we are thrilled. This is exactly what we’ve been looking for — challenging questions demanding reflective responses. However, we are in for a rude shock when the students’ reaction to the workbook is diametrically opposite. While they love the curriculum, thoroughly enjoy the activities and often remember their experiences and observations later, most students balk at the workbook. Some students simply ignore the work, others do a shoddy job in completing answers — giving laconic, unreflective responses, using large handwriting to easily fill lines, skipping questions, etc.

This problem could arise for several reasons, some unconnected with the Small Science workbooks per se. Most children try to avoid writing — across classes, across gender. Perhaps this is a facet of Al Qamar, which follows the Montessori method where there is not much emphasis on extensive writing in the early years. Perhaps it is a broader issue having to do with how we, as a society and community, value writing, whether as simple record-keeping or as a form of self expression.

Too much of a challenge?

The Small Science work involves mental effort in reading, understanding, framing a response which is free of grammatical errors and spelling mistakes, and in a good handwriting. Students are willing to give oral answers — even in depth answers. Or they are willing to write if the answer is given or dictated. But not both mental effort and writing. Possibly they / or the teachers set up very high expectations for themselves and get disheartened. And worry about having to correct their mistakes.

Sometimes the volume of work seems too much from a child’s perspective — each chapter in the Grade 4/5 workbooks is quite lengthy. And the questions are challenging. At a gut level we feel there is immense benefit in posing challenges, providing meaningful contexts and having children think and write, yet a general reluctance for the workbook appears to be a natural fallout.

Caveat : The issues we’re facing with workbook completion have been observed over the years. With trial and error and introduction of different techniques (see Inquiry to learning – 2), we have improved student response to the workbook assignments. However we have a long way to go.

For our own understanding, we need more systematic observation of whether the work becomes easier through the year as the students get used to completing the workbook sections. Additionally, we need to observe what happens as students graduate to a higher class each year. Does the gradient of difficulty of the curriculum match the students’ developing capabilities? Does the diversity of tasks suit a diversity of learning styles? Can we identify a level and quality of challenge to engage most students at most times?

Language for and through science

Traditional classroom teaching often requires students to mechanically copy questions as well as answers from the blackboard and to write standard essays on set topics. In contrast Small Science calls upon students to express their own observations, experiences, ideas, and inferences, first orally and then in writing. A major assessed aim of Small Science is language development for and through science. Over Grades 3, 4 and 5 the language development exercises include successively more critical thinking, argument and debate. The workbook is expected to be the vehicle for such development (see Small Science Class 4 Teacher’s Book, pp.9-21). We must document and assess whether the expected language development is happening, and what kind of scaffolding is needed for it to happen. In the meanwhile, here are some observations from our classrooms.

Different strokes

After the exciting activities and experiments, writing may appear to be a drudgery or children may feel the workbook work is unrelated to their science work. A clear case is AI, a 3rd grade student. He lives, dreams, eats and sleeps Small Science. It’s been a springboard for him to do several extension activities. He has on his own initiative started writing his observations on a snail, he talks to caterpillars, draws animals, etc. However, his workbook remained empty till I insisted he completes it. Once he started the workbook, he enjoyed it and went further with a lot of the questions — especially when it came to drawing, sticking feathers, bark rubbings etc. He took special effort on the observation of leaves and tabulation of bark colours, textures and living things on them (Small Science Work Book Class 3, p.13), working on it with his friend AM after school, both of them running out twice to observe the trees to check if their recordings were correct.

AI’s writing on a snail he watched at home

(AI, Boy, Grade 3)

The Montessori method allows an exceptional student like AI to follow and develop his own interests — which in this instance are catalysed by Small Science. Of course here too questions remain. How do we support the inner drive of differently talented students? How much can, and should we push them on the workbook without losing their interest?

Some children who like writing per se, enjoy the reflective pieces — it’s another opportunity to express themselves. AF, a 4th grade girl, is quite a shy child and usually buried in books. Rarely comes for teaching sessions or does written work in class. Interestingly she wrote extensively especially on the questions which required long responses. So did IAA, who demonstrated a way with words and ran out of space to write. In contrast, MA and SfS, also bookworms, and bright, articulate children, wrote short abrupt responses. I recall that last year MA and SfS typed out their own novels for NaNoWriMo — an international novel writing competition. Perhaps the glamour of NaNoWriMo was a factor in their overcoming their inertia. Or like many students who are more exposed to computers, these students may prefer typing to writing with a pencil.

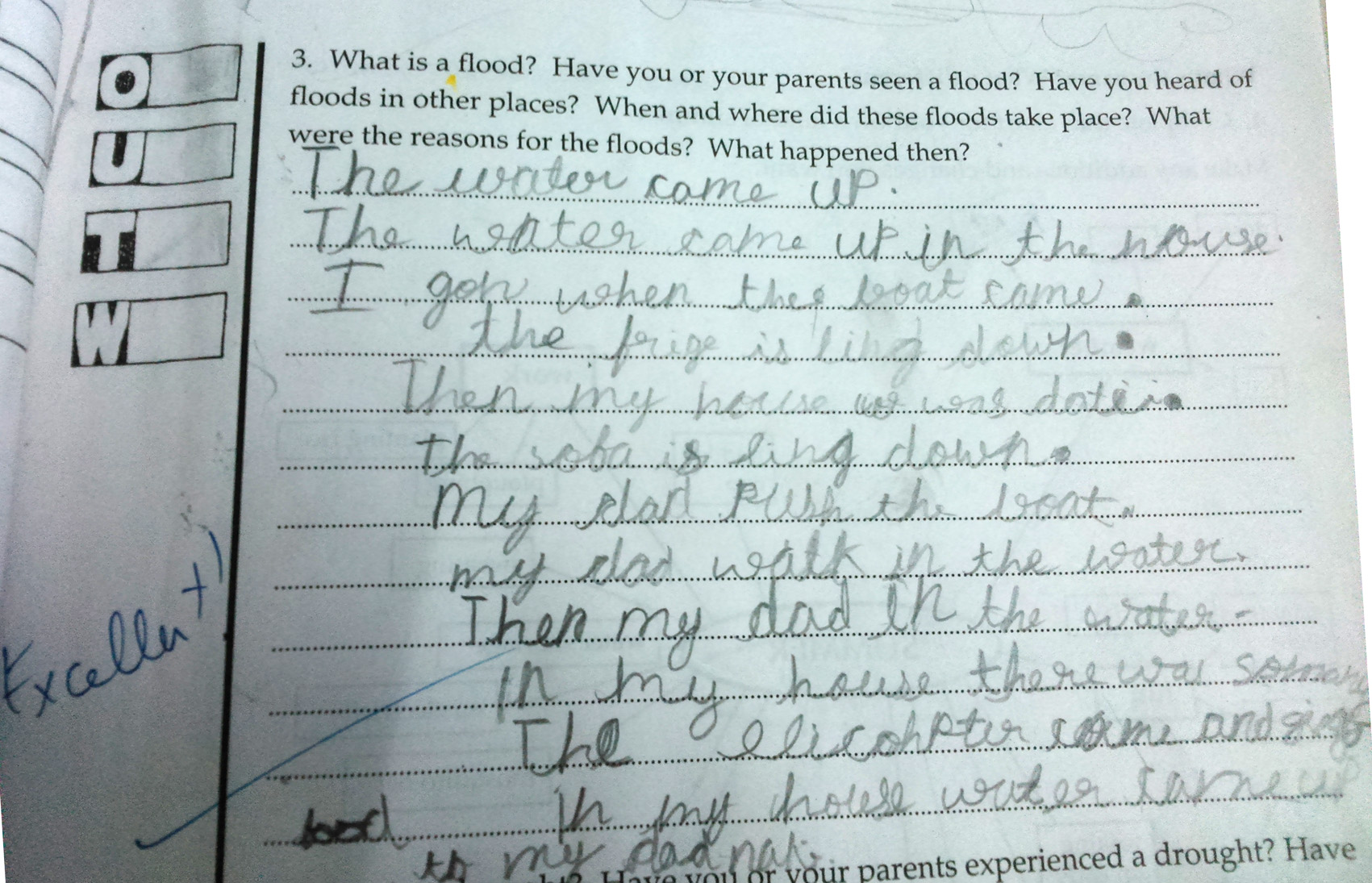

Sometimes children write in detail about an experience or subject close to their heart. The sudden and destructive Tamil Nadu floods of November 2015 impacted our students as they did all citizens. Some of the most articulate responses of the students on this subject are in ‘Responses on Weather‘. A striking case is of ShS, who is otherwise a reluctant writer. ShS came up with a poem-like response which described in detail what happened when the flood waters entered his home.

ShS’s writing on the floods

The water came UP.

The water came up in the house.

I gon when the boat come.

The frige is ling down.

Then my house was date.

The sofa is ling down.

My dad push the boat.

My dad walk in the water.

Then my dad in the water.

In my house there was so many water.

The helicopter came and gave food.

In my house the water came up to my dad nak.

(ShS, Boy, Grade 4)

We have noticed in some cases, when students give very good responses, they themselves are not aware of having done something remarkable, may look puzzled when the teacher shows her appreciation and may later carelessly misplace their wonderful writings or drawings. Getting students to recognise their own capability is another challenge we face as teachers. It’s part of metacognition, we guess, and will come with time.

Some students with learning disabilities and attention issues have trouble with writing tasks. In such cases we encourage parents to seek professional diagnosis and treatment.

Students with poor handwriting naturally shy away from writing. For these the Montessori method prescribes clay work, cutting patterns in paper and a handwriting book, to which we add, gentle coaxing with the workbook.

Second language

Coming back to language issues, sometimes students don’t understand the question — reading comprehension is challenging for those for whom English is a second language, and less spoken at home. The first step is explanation of the question in Tamil; the children then have difficulties in framing responses in English for the same reason. Despite recounting to them about Tamil being an ancient and beautiful language, we cannot escape the fact that English has a privileged position in society and among the students’ peer group too. Also there is a difficulty when the teacher’s own language is not Tamil. Calling attention to a student’s language challenge in the whole class may only lead the child to withdraw further. Individual attention later by a co-teacher works to an extent.

Language as analytical tool

Even in students for whom English fluency is not an issue there is a visible lack of attention to detail — in reading comprehension — and in answering the questions — students just give a response that they assume is required. This is seen for example in the questions where students are asked to write two similarities and two differences — many write a single similarity/difference across 2 lines, eg. 1) Butterfly has 6 legs 2) Spider has 8 legs.

At the Vedavalli Vidyalayas too teachers find that workbook writing is a challenge for students. However in some respects their experiences are different. Here the students are predominantly Tamil speaking and the teachers too are comfortable in Tamil. Although in the classroom English is mandated, its social privileging is less obvious. Further, pre-discussion of workbook questions is more of a norm than it is at Al Qamar. When it comes to the questions on similarities and differences, all the teachers report that students really enjoy the oral discussion, vying with each other to come up with more and more differences and similarities, some of which later find place in their written responses.

Questions on similarities and differences (What’s the same, what’s different and Find the odd one out) are meant to develop skill of critical observation and generalisation. Noticing similarities involves abstraction, and is more difficult than noticing differences (Small Science Class 4 Teacher’s Book, p.10). Pre-discussion has an advantage that it provides scaffolding and peer support, but our concerns remain, that all students must think on their own and not copy responses.

Vocabulary and terminology

As the students write their own responses, their answers are framed in their own vocabulary, which is usually inexact and imprecise. We do not worry too much about this as the focus is on having children express their observations rather than giving “trained” answers. At the same time in oral responses we often ask for clarifications, which the students are usually perfectly capable of providing, and it sensitises them to precise expression and shades of meanings.

Our students rarely use scientific terms. In fact, I’d be worried that an adult did the work if the answer was too “scientific” or that the child wrote on the basis of what s/he “read” rather than observed. An example is, responses after plotting sunrise / sunset timings during the summer and winter which came out too pat as, “the days are longer in summer and shorter in winter.” Book knowledge also dictates, “there are four seasons including autumn and spring.” We’d rather have the students say, “In Chennai it’s hot all through the year, except when it rains…”

Continued in ‘Inquiry to learning – 2‘.

Aneesa Jamal

Correspondent, AQA

Jayashree Ramadas

Visitor from HBCSE